Mahoning schools work to cut high absence rates

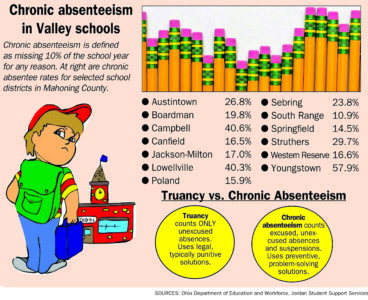

Chronic absenteeism — defined by the U.S. Department of Education as missing 10% or more of the school year — has emerged as one of the most persistent and complex challenges facing public education nationwide.

The issue intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, when school disruptions, health concerns and family instability drove absenteeism rates to historic highs. Although national figures have improved since then, attendance has not returned to prepandemic norms and many communities continue to grapple with the long-term consequences.

Nationally, chronic absenteeism peaked at approximately 31% during the 2021-22 school year before declining to 23.5% in 2022-23. That remains well above the prepandemic rate of about 15%.

Ohio mirrors this trend. According to state report cards, 25.1% of Ohio students were chronically absent during the 2024-25 school year, which is nearly double the state’s target rate of 12.8%.

A September 2025 report from Thomas B. Fordham Institute found that roughly 1 in 4 Ohio students — about 400,000 children — missed at least 10% of the school year. Those statewide averages, however, conceal stark regional disparities. Lorain recorded the highest chronic absenteeism rate in Ohio, followed closely by Youngstown, where more than half of all students were chronically absent.

That reality makes chronic absenteeism especially urgent in the Mahoning Valley, where attendance challenges extend well beyond Youngstown itself. In Youngstown and neighboring districts — Lowellville, Struthers, Boardman, Campbell and Austintown — educators are confronting the problem with a range of strategies shaped by local circumstances, resources and philosophies. While approaches differ, a common theme emerges: absenteeism is rarely about apathy. Instead, it is often rooted in transportation barriers, mental health struggles, family responsibilities and trauma.

YOUNGSTOWN

The Youngstown City School District continues to be proactive regarding tackling chronic absenteeism, which peaked around 71% during the COVID-19 pandemic. The rate, however, decreased to 57.9% last year and is projected to drop to 54% or 55% this year, Superintendent Jeremy Batchelor said. He also noted that the chronic absenteeism figure in Ohio takes into account excused and unexcused absences.

While the lower figures show improvement compared to several years ago, “it’s still way too high,” Batchelor added.

As a result, the district has an academic team in place that consists of attendance assistants, social workers and counselors in all of the buildings who meet weekly and regularly track and check in on students as necessary, he said.

In addition, the district is continuing to implement the Cleveland Browns’ Stay in the Game Attendance Network, which the Youngstown City Schools adopted five or six years ago, Batchelor said.

The initiative, launched in 2019 and in conjunction with the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce and Harvard’s Proving Ground, is partnered with more than 220 districts and offers tools, resources and a variety of incentives to encourage consistent attendance. Such resources include attendance trackers, yard signs and in-school events to celebrate good attendance.

Other ways the district is trying to tackle the problem is via having specialists sent to other school districts in Ohio to glean what is working for them, as well as working to ensure the curriculum is strong and engaging, Batchelor said.

Another contributor to the attendance problem is that some students, especially those of Spanish descent, fear possibly being arrested and deported, as reflected in what has been the case in Minneapolis and elsewhere across the country, the superintendent noted.

AUSTINTOWN

Chronic absenteeism remains one of the most persistent challenges facing Austintown Local Schools, where district leaders say family dynamics, student disengagement and limited enforcement under state law continue to complicate attendance efforts.

Kathy Dina, Austintown’s director of security and truancy, said the district expanded its approach after county-level truancy support was eliminated because of funding cuts. Over the past three years, Austintown hired its own truancy officers and added attendance coordinators at every school level.

“We track attendance closely, send letters, and try to understand why students are missing school so we can resolve the issues,” Dina said. “If there’s something we can fix — transportation, clothing, food — we do it.”

Despite those efforts, Dina said parental involvement remains the district’s biggest challenge. While Ohio law requires parents to ensure school attendance, enforcement is inconsistent.

Dina said absenteeism increases with age, with middle and high school students most affected. Students receiving special education services also face higher attendance challenges. A common cycle emerges: Students miss school, fall behind academically, become anxious or overwhelmed, and then miss even more days.

Mental health concerns are frequently cited by families, often alongside claims of bullying or anxiety. Dina said district staff investigate those claims carefully and work with students to create accommodations when appropriate. However, technology has intensified many problems.

“Students are exhausted,” she said. “They’re up all night on their phones or gaming.”

Austintown emphasizes early intervention through counseling, incentives, referrals to community agencies, and coordinated planning among principals, counselors and truancy staff. Incentives such as room parties and tickets to YSU sporting events have shown promise, though Dina said staffing limitations remain a barrier.

Still, Dina believes stronger accountability — particularly for adults — is necessary. “Attendance affects everything,” she said. “Academics, mental health, friendships. If students aren’t here, they’re missing far more than lessons.”

BOARDMAN

In Boardman Local Schools, Superintendent Chris Neifer said chronic absenteeism tends to increase as students move into upper elementary and secondary grades. Attendance challenges often begin with just a few missed days early in the year and compound if left unaddressed.

Health concerns, housing instability, transportation barriers and mental health needs all contribute. Since the pandemic, anxiety and school-avoidance behaviors have become more prevalent.

Boardman emphasizes early outreach, individualized problem solving and strong relationships with families. The district partners with HWS Best Health Services and employs 15 in-house counselors and caseworkers. Each school has an Attendance Intervention Team that monitors data and works directly with families.

Those efforts have produced results. Chronic absenteeism has declined from 21% to 19.8% over three years, below the state average. With additional funding, Neifer said the district would expand mental health services and attendance focused staffing.

“Attendance is about more than being in a seat,” he said. “It’s about support.”

CAMPBELL

Superintendent Matthew Bowen of Campbell City schools said attendance challenges are not evenly distributed, and like many districts across Ohio, they do see some student groups facing more obstacles to consistent attendance than others.

“What matters most is how we respond. Day to day, student engagement in our schools is stronger than it has been in years. Students want to be here,” he said.

Bowen said expanded STEM programming, a growing number of clubs and activities, increased College Credit Plus opportunities, and more before- and after-school events have helped create a culture where students feel connected, supported and challenged. When safety, climate or bullying concerns arise, they are addressed through established protocols and student support.

“We focus heavily on early intervention, using data and building-level attendance teams to identify warning signs and work closely with families before absences become chronic,” Bowen said.

At the district level, Bowen said they have actively participated in the state’s Attendance Taskforce and continue to work alongside partners at the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce and community organizations, including the Cleveland Browns, who “consistently remind us that attendance is a team sport.”

That collective approach is producing results. Compared to last year, Campbell reduced overall chronic absenteeism by approximately 2.5%, reduced the number of students who are severely chronically absent by 2%, and increased the percentage of students with satisfactory attendance by 2.6%.

Bowen added, “While challenges such as transportation, health needs and family circumstances remain part of our work, we view those barriers as opportunities to create stronger supports for students. Through partnerships offering wraparound services in health, nutrition, and social-emotional support, and a shared commitment across schools and community, our district growth is better than similar districts across the state. That progress reflects a team effort focused on helping students show up, stay engaged, and succeed.”

LOWELLVILLE

In Lowellville Local Schools, chronic absenteeism is most pronounced at two pivotal transition points: sixth grade and 12th grade. Superintendent Christine Sawicki said those grades post the district’s lowest attendance rates and highest levels of chronic absence during the 2025-26 school year.

Transportation remains the district’s most significant barrier. About half of Lowellville’s students are open enrolled from outside the district, and many families struggle with reliable transportation.

“Mental and physical health challenges also play a major role,” Sawicki said.

Rising anxiety and other mental health needs have led some students to miss school for treatment, including inpatient and outpatient care.

“Supporting students’ mental health is essential not only for their well-being but also for helping them stay engaged in their education,” Sawicki said.

Lowellville has begun seeing early progress through partnerships focused on intervention rather than punishment. Referrals through the Juvenile Court’s Early Warning System have produced “small but meaningful” gains, while daily in-school social work support through Alta and campaigns with the Cleveland Browns “Stay in the Game” initiative provide additional outreach.

The district monitors attendance weekly and convenes a Student Assistance Team when patterns of absence emerge. Counselors maintain long-term relationships with families, and a behavioral health and wellness coordinator helps connect them with services.

Still, Sawicki acknowledged that reminders and incentives alone are not enough. “Attendance challenges often stem from deeper, individual circumstances,” she said.

If additional funding were available, she would expand transportation options, increase mental health services and hire a full-time attendance officer.

STRUTHERS

At Struthers Middle School, attendance patterns tend to fluctuate around the school calendar rather than clustering within specific grade levels or student groups. Principal Dave Vecchione said the district saw notable improvements after eliminating partial school days — a change that reduced confusion and encouraged consistent attendance.

Still, absences often spike in the days leading up to scheduled breaks. To address those trends, Struthers relies on a dedicated attendance team made up of administrators, counselors and teachers. The team regularly reviews attendance data, tracking both excused and unexcused absences by grade level to identify emerging patterns before they become chronic. When concerns arise, staff meet directly with students and reach out to families through phone calls, letters and postcards.

“We focus heavily on relationships,” Vecchione said. “If students feel known and supported, they’re more likely to show up.”

One of the district’s most effective tools has been its Check-In / Check-Out program, which provides students with consistent adult mentorship and accountability throughout the school day. Students meet with a designated mentor in the morning to set goals and again in the afternoon to reflect on their progress. According to district officials, the program has led to measurable improvements not only in attendance, but also in academic performance and behavior.

For students with more significant attendance challenges, Struthers may refer families to the Mahoning County Juvenile Court’s Early Warning System. Additional supports include on-site mental health services through PsyCare, a student and staff wellness counselor, and family assistance through the Dr. Ray Barnett Care Closet and a food pantry operated in partnership with Second Harvest Food Bank.

Yvonne Wilson, a juvenile diversion officer who works closely with Struthers schools, said the personal connection built through daily check-ins is often transformative.

“When students know someone is paying attention every single day, it changes how they see school,” Wilson said. “They feel accountable, but they also feel cared about.”

Wilson said students frequently cite transportation problems, anxiety and difficulty coping with stress as reasons for missing school. By listening closely to those concerns, staff are better equipped to communicate with families and connect them to appropriate resources before absenteeism becomes entrenched, she said.

Superintendent Pete Pirone said Struthers’ chronic absenteeism rate has declined modestly over the past three years, though it remains higher than prepandemic levels. After peaking at 33% during the 2022-23 school year, the rate has edged downward, with the high school reporting the highest levels of chronic absence.

Pirone identified transportation challenges, rising student anxiety and older siblings missing school to care for younger children as the most common drivers of absenteeism. Since the pandemic, he said mental health needs — particularly anxiety — have had a profound impact on attendance.

The district has set a goal of reducing overall chronic absenteeism by 3%. The middle school met that target last year. With additional funding, Pirone said, Struthers would hire a full-time staff member dedicated solely to attendance intervention.

Middle School Guidance Counselor Floyd Cracraft echoed many of those observations. He said transportation issues, anxiety, stress and family-related challenges are the most common factors behind chronic absenteeism. He has also seen a marked rise in student anxiety since the pandemic.

“Attendance issues are rarely simple,” Cracraft said. “Sometimes families are making tough choices — like scheduling vacations during the school year because that’s the only time they can afford. It’s complicated.”

JUVENILE COURT APPROACH

In response to rising concerns about chronic absenteeism, school districts across Mahoning County are partnering with the Mahoning County Juvenile Court through its Early Warning System (EWS), a program designed to intervene early and keep students engaged in school before attendance issues escalate into court involvement.

The Early Warning System, overseen by Director Michael Massucci and supported by Magistrate Gina DeGenova and Judge Theresa Dellick, focuses on identifying attendance, behavior and academic concerns at an early stage. The goal, officials say, is support, not punishment.

“Problems are much easier to solve when they’re addressed early,” Massucci said. “Most partner schools refer students after just two or three days of concerning attendance patterns so we can intervene before the situation becomes more serious.”

Under the program, students who accumulate more than 45 hours of unexcused absences may participate in an on-site EWS Review Hearing conducted at their school. DeGenova travels to partnering districts to hold these hearings, which began at the start of the 2025-26 school year. If a student reaches more than 72 hours — roughly 10 days — of unexcused absences, a formal hearing may be scheduled at the Mahoning County Juvenile Court.

While unexcused absences trigger hearings, court officials emphasize that excused absences also count toward chronic absenteeism. In cases involving high numbers of excused absences, families may still be contacted by EWS staff to identify challenges and connect them with support services before any court action is considered.

Parents and guardians are required to attend all hearings. According to court officials, formal charges are considered a last resort and are only pursued if attendance does not improve despite repeated interventions.

Once a school makes a referral, a court-assigned worker contacts the student, family and school to build trust and assess the situation. The worker helps develop an individualized plan, often linking families with counseling, transportation assistance, or in-home services. The emphasis is on removing barriers to attendance rather than assigning blame.

If attendance concerns continue, DeGenova may convene meetings with the student, family and school officials. Wearing her judicial robes, she explains the legal requirements of school attendance, explores underlying issues and outlines potential consequences. These can include community service, suspension of driving privileges for students, required counseling or school placement changes. However, officials stress that punitive measures such as fines or jail time are rarely effective.

“Fines and incarceration often make absenteeism worse,” Dellick said. “They can create financial hardship, lead to family instability or even place children into foster care. We do everything possible to avoid pulling families deeper into the court system.”

Court officials report that the most common causes of chronic absenteeism include transportation problems, child care responsibilities — such as older students caring for younger siblings — mental health challenges, trauma, and, in some cases, bullying. Bullying can be particularly difficult to address, as students and families may fear retaliation.

The results have been significant. Since the Early Warning System expanded in 2018, juvenile delinquency cases in Mahoning County have dropped from approximately 2,000 to about 200.

Dellick said she is encouraged by the level of cooperation from parents and the results. “When families, schools, and the court work together,” she said, “students are far more likely to succeed.”

Correspondent Sean Barron contributed to this report.