Students inspired by local history

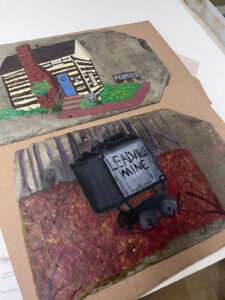

Submitted photo These are examples of student “folk art” done on slates, which was inspired by a recent visit to the Austintown Historical Society.

AUSTINTOWN — A partnership with the Austintown Historical Society is helping local students see art history not as a distant timeline of famous works, but as a living reflection of community life.

That idea came into focus when Austintown art teacher Mike Hornyak teamed up with Harold Wilson, a former Austintown educator and active member of the Austintown Historical Society. What began as a conversation about local history quickly evolved into a hands-on learning experience that connected students to Austintown’s earliest days — and challenged them to think differently about the role of art in society.

Hornyak, who teaches art history and art appreciation, said he grew increasingly aware that students often completed the course with limited understanding of how art functions beyond museums and textbooks. Rather than continuing a traditional survey of artistic movements, he restructured the curriculum around thematic inquiry — exploring how universal human ideas such as love, fear, worship and politics are expressed through art across time and cultures.

During the fall semester, the guiding concept became clear: art reflects the community and the community reflects art.

Wilson’s suggestion to collaborate with the Austintown Historical Society proved to be a natural extension of that theme. Through the partnership, students were able to engage directly with local history by visiting two of the society’s most significant sites — the Austintown Log Cabin and the Strock Stone House soon after the holiday break.

At the sites, students observed firsthand how early settlers lived and worked after Austintown’s settlement around 1793. Rather than encountering art as framed paintings or sculptures, they discovered it woven into daily life — visible in handcrafted tools, furniture, textiles and architectural details created out of necessity, rather than decoration.

“The experience helped students understand that art doesn’t always announce itself,” Hornyak said. “In early American communities, creativity was functional. It served survival, faith and identity.”

That historical grounding led to the project’s second phase: using art as a tool for preservation and community support. Inspired by their visits, students created original artwork on reclaimed slate tiles, drawing imagery and symbolism from the Log Cabin and Stone House. The completed pieces will be donated to the Austintown Historical Society to be sold or auctioned as a fundraiser, with proceeds supporting the maintenance and preservation of the historic sites.

Before beginning their studio work, students explored the broader artistic context of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Hornyak contrasted the formal European movements of the time — such as Neoclassicism and Romanticism — with the realities of early American frontier life.

“As a newly forming nation, America’s focus was survival and development,” Hornyak said. “Art was present, but it was often created by self-taught immigrants with little formal training. We talked about approaching the work with empathy and adopting a naive or folk-art style that reflected those circumstances.”

That approach encouraged students to prioritize authenticity over technical polish, reinforcing the idea that art’s value lies in meaning and purpose as much as skill.

The Austintown Historical Society, a volunteer-run organization, preserves the township’s heritage by maintaining and opening the Austin Log Cabin and Strock Stone House for public tours. The society also curates educational exhibits — such as a one-room schoolhouse display — hosts community events and partners with local schools to bring history to life for new generations. Fundraisers and donations, including projects like the student artwork, play a vital role in supporting these efforts.

For Hornyak, the success of the collaboration goes beyond the finished pieces.

“Sometimes students recognize the importance of a project right away, and sometimes it takes years,” he said. “But teaching art history through a single conceptual thread allows for deeper connections — between past and present, between art and community, and between students and their own lived experiences.”

The student-created slate artworks will be donated to the Austintown Historical Society, continuing the cycle of learning, creativity and preservation that brought the project to life.