Culture, histoary marinate inside local cookbooks, librarian says

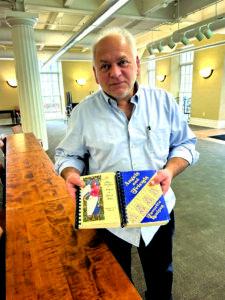

Tim Seman shows examples of popular local cookbooks during his presentation Saturday titled “Community Cookbooks: Food, Memory, and Tradition” at the Poland Library. Correspondent photo / Bill Koch

POLAND — A dozen people braved the cold Saturday morning to hear a presentation on “Community Cookbooks: Food, Memory, and Tradition” at the Poland branch of the Public Library of Youngstown and Mahoning County.

Librarian Tim Seman gave the presentation as part of the library’s America250 series in commemoration of our country’s semiquincentennial.

Seman grew up on the South Side of Youngstown and since childhood has been interested in the accumulated knowledge of a culture. It started when his uncle told him to get in the back of a pickup truck to go mushroom hunting. When Seman asked how they knew they wouldn’t pick poisonous mushrooms, the answer was, “We know what to do.”

Local cookbooks likewise are an expression of what people in a community learn and pass on to others.

The earliest American cookbook was written by Maria Moss in 1864, published as a fundraiser for wounded soldiers returning from the Civil War. This started a trend as most local cookbooks are fundraisers for churches and other organizations.

Seman pointed out differences in earlier cookbooks. For example, the oldest ones only list ingredients that can typically be found in the home. This includes the pride many homemakers would take in making their own mustard and “catsup.”

Older cookbooks would often contain other household hints, such as antidotes to poisons or how to “mend broken dishes.”

Some of the outdated terminology requires definitions, as recipes might include measurements such as dessert spoon, wineglass and gill (one half cup). Because older stoves did not have temperature gauges, directions might be slow oven (300-325 degrees) or fierce oven (475-500 degrees).

More recent cookbooks started adding ingredients that could be purchased at the grocery store. It is helpful for dating the publication when recipes include items such as Jell-O or Cool Whip. They also started to include simpler meals for women who worked outside the home, but were still expected to come home and make dinner.

Besides what cookbooks teach about food and culture, they are also an excellent resource for genealogy. Since they include submissions from individuals, they are considered to be a “primary source.”

Seman showed the audience how to use www.libraryvisit.org to do genealogical research. Women used to identify themselves with their husbands’ names, such as “Mrs. John Smith,” so a search needs to start with the man’s name to get to his wife. Seman was able to use The Vindicator records to find out the identities of individual contributors.

Cassie Slaybaugh of Youngstown said she has been “using library resources a lot” to learn local history. She said she loved the presentation as it showed how much information can be gleaned from a cookbook.

Kathleen Holden of Canfield said she has been to several of Seman’s presentations and was fascinated by his wealth of information. She was excited when he was able to immediately pull up a copy of a cookbook she contributed to in 1988 for the Holborn Herb Growers Guild.

Seman said while he enjoys reading and using the recipes, cookbooks represent “what it was like for a community to band together to build the middle class.”

Seman has an upcoming three-part presentation about Industrial Heritage (Feb. 18), Deindustrialization (March 18), and a public forum about the Valley’s future (April 15), which will include Youngstown Mayor Derrick McDowell, State Rep. Lauren McNally, D-Youngstown, and Ian Beniston, executive director of the Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation. They will all be at the main library in Youngstown from 6 to 7:30 p.m.